The Tulip Lifecycle

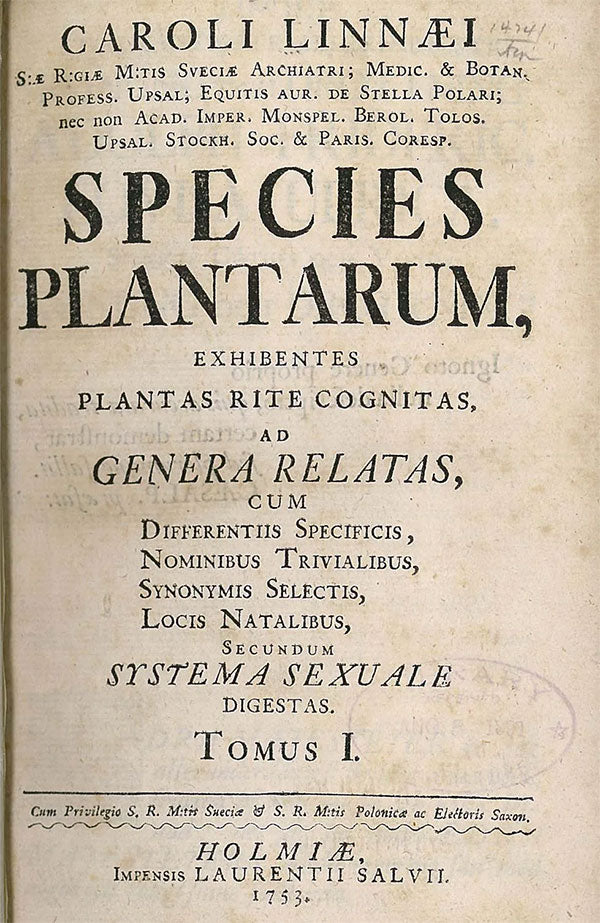

For years, the tulip confused and confounded its admirers and students who couldn’t decide if it was a lily, a narcissus or something entirely its own. Today, we organize and name tulips according to a system based on the work of Carolus Linneaus, a Swedish botanist and zoologist.

The work of Carolus Linneaus

Linneaus established a hierarchy that groups living organisms by kingdom, class, order, genus and species. Modern taxonomy has added several additional categories so that tulips are now classified in this way:

- Kingdom Plantae – Plants

- Subkingdom Tracheobionta – Vascular plants

- Superdivision Spermatophyta – Seed plants

- Division Magnoliophyta – Flowering plants

- Class Liliopsida – Monocotyledons

- Subclass Liliidae

- Order Liliales

- Family Liliaceae

- Genus Tulipa L.

- Species (there are roughly 75 known species of tulip today)

- Cultivar

To this, we add specific names for unique varieties or cultivars. Plants are commonly referred to by their genus, species and cultivar. For example, the tulip Tulipa clusiana actually takes its species name from the early botanist Carolus Clusius. Here’s one cultivar of that species: Tulipa Clusiana Lady Jane, which may also simply called a Lady Jane tulip.

Species and Hybrids

Species tulips are tulips that can produce fertile seeds that “come true,” producing plants identical to the parent. Today, it is quite possible to fill a garden with species tulips that have existed relatively unchanged for a thousand years, but tulip lovers across the centuries have focused their obsessions on hybrids.

Crossing two species creates hybrids. Over the centuries, tulip hybridization has created many complex and beautiful tulips, ranging from the needle-like flowers favored by the Turks to Rembrandt tulips, which approximate the elaborately flamed and striped blooms that fueled Tulipmania. Since hybrids rarely produce identical offspring through seeds, propagation of these varieties relies on bulb division.

How to Make a New Tulip

Many species tulips will hybridize naturally, but today breeders create most new tulips in a carefully controlled process that can take years. Here’s how it works:

The breeder selects the parent flowers, giving consideration to factors such as size, flowering season, shape, color, disease resistance, and growth rates.

When the “father” bulb flowers in the spring, the breeder carefully removes their stamens, collecting and drying the pollen that clings to their anthers.

When the mother plant blooms, the breeder protects the flowers from all pollen sources, waiting until the stigma grow ripe and sticky. Then the breeder carefully brushes dried pollen from the father flower onto the pistil. Afterward, the breeder again protects the mother plants from all other sources of pollen, allowing seedpods to develop and ripen. Once the seeds are ripe, the breeder collects and dries them, ultimately saving only the healthiest.

In early winter, the new seeds are planted in pots filled with fine soil. It must be kept at a cool temperature for several months as tulips need a cold period to grow or bloom well.

The first year, tulip seeds produce a thin, grassy leaf along with a tiny bulb no larger than a pea. The breeder selects the fastest growing bulbs, lifting them from the soil in summer, drying them and then replanting in the fall. The breeder must repeat this process for several years as most new tulips won’t produce a flower for four to eight years.

When the new bulbs finally bloom, the breeder begins the process of positive selection, choosing those with the most appealing characteristics for continued growing. Breeders also rely on negative selection, weeding out weak or ill-formed plants. Each selected flower gets a label with a unique code and notes on the parents and year of hybridization.

The breeder continues to grow selections on for several more years continuing to weed out the less desirable plants. Hybridization is a slow and painstaking process. After the five to eight years involved in bringing new varieties to flower, a breeder who has made 100,000 crosses, may find just five new varieties worth bringing to market. Once selected bulbs have reached maturity, they receive names and the process of propagating the named flowers begins.

Propagating Tulips

Hybridized tulips do not produce seeds that “come true” or grow to resemble their parents. The only way to multiply a tulip is to clone it by separating offsets, small bulblets that typically grow in clusters of two per healthy bulb. These are grown on to produce more offsets, which are again grown on to produce even more. Some varieties produce more offsets than others, but because of this process, it can take 20 to 30 years to bring a new tulip to market.

It may seem improbable that this process could ever yield enough bulbs to satisfy commercial markets, but over the course of 25 years, it is possible to build a huge inventory.